Scratch’s kickdrum: thoughts touching on the Upsetter’s special sense of things

I have in my possession a stupid quantity of music by the Jamaican record producer, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. Look at it. There is a hefty sofa under that lot… But why? What can it possibly all mean?

I HAVE BEEN persuaded by a very old friend to try to explain, for our own benefit at least, why people like us love Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry as much as we do.

“And who might Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry be, when he’s at home?”

I can hear my grandmother uttering these words, her face a picture of disdainful incuriosity. Not quite Lady Bracknell, but not unlike how I imagine Queen Victoria might have sounded when presented with difficult questions about who’s who in reggae.

“Well, Gran,” I can also hear my younger voice responding with controlled deference. “Lee Perry was a man my friend Simon and I now regard as the greatest of all the producer-engineers to push against the splintered boundary boards of Jamaican rhythm; a co-inventor of reggae for sure but also by far and away Jamaican music’s most unfettered ear.”

“I beg your pardon?“ says my grandmother, who is not as deaf as she affects to be. “A fetid rear? I have never heard anything quite so repulsive in my life. No! Not another word. I do not care to learn another thing about this man and his unsavoury behind, whether he was a co-inventor of reggae or not.”

And having taken that on the chin, I also feel compelled to take issue with myself for the lazy use of language in the first sentence of this essay. Do I love Lee Perry (also known to himself and others as The Upsetter)? No, I don’t — it was a silly thing to say, and ill-advised to start an essay with an ad hominem declaration of love. I may love Perry’s music wildly but the same cannot be said for the man. I met and interviewed Scratch on one occasion only, getting on for thirty years ago, and you wouldn’t have said it was love going on in the room that day, not by any stretch. I did not dislike him; there was simply no connection made, at any level. I came away with very little sense of the man behind the projected man, except in a couple of superficial senses. He was tiny, he was inscrutable and I am pretty sure he was taking me for a mug’s ride. He rather imagined, I think, that if he tossed me a few bits of weird fish, I’d swallow the lot, lollop off like an obliging sealion and regurgitate them in the newspaper I then worked for, as if bits of old fish were some kind of essential marvel of lore, as Scratch himself did indeed appear to believe.

The reality is that I have no feelings either way for Perry, in high contrast to the way I feel about the hundreds of recordings he made over the span of four, or is it, five decades for a multitude of record labels? Yes, five decades. I love the sound he coaxed into the world with his alchemical way of aligning his forces with the forces of Nature. I admire his determination to maximise the efficiency of the technology required to make those recordings sound as if they were infused with something beyond the technological — and to use only the simplest methods in imparting new angles and textures to the commonplace world we see and hear, or think we see and hear. I am less awed by his claim to have blown ganja smoke into his microphones to enhance their performance, and not at all by the volume of human seed (presumably his own) he spilled into the foundations of his Black Ark bunker studio as it was being constructed — and consecrated— behind his house in Kingston, JA, in 1973. And of course there is the question of why he burned the Ark to the ground in 1978. It’s a parcel of yarns fit to embellish any Bildungsroman and, really, it doesn’t matter a jot whether the yarns are true or not: you still have to learn how to listen to Scratch’s music and appreciate it for what it is (an ability incidentally that, once gained, stays with you for life, like riding a bike). You have to do the work. And only then is it possible to separate the man from his follies and you from your own preconceptions based on all those hectoring appeals made to your baser anthropological instincts. By then, some sort of a connection will have been made and a message received; a connection invested with a strange but persistent feeling for life.

Thus begins the Scratch experience. There is both clownishness and extreme seriousness in all of it — the surrealism of the everyday and the banal, expressed with thick, circulating ropes of beautiful rhythm, almost as if beautiful rhythm were the only way to address the very hardest and most pressing questions you can conceive of. And alongside this rather elevated way of trying to capture this strange man’s actual purpose, there has existed, always, an abiding temptation to cast Scratch in the role of some kind of insular oracle-cynic, one which he was always more than happy to support if it helped bring his amazing music to market. Them’s the breaks.

What’s not to like, then, for a pair of provincial middle-class grammar-school white boys who once inclined to position themselves at oblique angles to the schoolboy herd? Virtually nothing, is the answer. Even if Scratch was no kind of an oracle, he certainly qualifies as a genius according to the conventional 21st-century usage of the word — but I much prefer to think of him replete with ‘genius’ in the way Shakespeare would have understood it, and the Romans before him: genius as an expressive guardian spirit of a certain sense of things.

Perry’s sense of things was what made his music live in the peculiar way it did, and still does even though he himself is no more. The kingly garb he wore and the regalia and the fish arranged with rocks and trinkets and pink and baby-blue images of the Virgin surrounded by Christmas tree lights in a portable display case were all very amusing in the moment of contact and perhaps might even snare the odd wishful ‘interpretation’ from devotees of the cult, but they don’t to my mind deliver goods you can do anything with, however wishfully you might feel that they must carry in their winking, spooky inertia some spark of voodooism. I’m sorry. No. The music does that job. The rest is décor.

On the other hand, it is important to recognise that the nature of Lee Perry the Man is pertinent to how the music sounds. Of course he is pertinent to it, as a father is pertinent to how a son goes about in the world. But I sometimes think that in the case of Scratch, the music is a longed-for father to the child in the man who made it. Lee Perry made his music the way he did because something in him needed to become a child, a child in the form of a little man, and then a little old man. To live an inverted life. To learn, as he proceeded through it, how better to really play.

There is undoubtedly something of Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince about Scratch, in as much as his surrealism is not surrealism to him but an expression of the world as the child in him needs it to be. This is the element of Scratch’s self-mythologisation that is harder to dismiss, I think, not least because it is involuntary mythologisation. Unfortunately he is no longer around to ask — I missed the chance when I had it.

REGGAE HAS A well-understood, if imprecise, point of origin — or, as some would prefer to contend, an imprecise point of originating error. The um-chah um-chah metre of a certain kind of rolling New Orleans R&B in the 1950s — typified gloriously by Fats Domino — reached deeply into the Caribbean soul via the long fingers of broadcast radio located in the Southern States of the US, touching the nearest shores of the island of Jamaica and extending inland. This was a Jamaica that was girding itself excitedly for approaching independence from British governance; a Jamaica that had sufficed itself musically for decades with the busy rhythms and story-telling of mento and calypso. And American R&B. Prior to this great moment, Perry had been growing up in Kendal in the parish of Hanover, which stood a little inland from the nearest north-western shore of the island, the one facing Florida and the Gulf of Mexico beyond the hulking obstruction of Cuba, itself in the early 1960s a place of tumult and change. Scratch had been a junior factotum in the record business for three or four years when the day marking Jamaica’s great leap into liberty finally arrived in 1962, accompanied by the bouncing energy of the hard-edged, shouty new island groove, known as ska.

“Um-chah um-chah” went the entire island over a bassline hit firmly on the Um, and the chopped off-beat chord hacked on electric guitar grew and grew in emphasis, sometimes doubled on piano and/or horns (woof!), as it gulped Fats Domino down the wrong way and choked him back up subtly changed. Walking bass now drove the music forward, the off-chop held it in equipoise — and where the genial Fat Man rolled and swung, Jamaica skanked faster and faster till the music pumped like pistons and those who concern themselves with such things looked at one another and declared that this was not R&B anymore. This was something else altogether.

One can only presume as a citizen of the UK, and never having lived through a season of national jubilation of our own, that it was because the entire Jamaican population grew weary of being excited that we came to know the warming, chilled-out vibe of ‘rocksteady’, which billowed over the horizon in 1966 to rock slowly and steadily on deeper currents of bass than ska ever rode, plus a more developed sense of melody — and more often than not a sunny smile. It was almost as if the Caribbean Tourist Board had stepped in and taken over the music industry in Jamaica. Love and sunshine? Blue sea, white sand? Come and get it! The Jamaicans, The Paragons, The Techniques, The Silvertones, Phyllis Dillon, Delroy Wilson and Alton Ellis… Rocksteady snicked ska down two gears and headed for the nearest hammock. You climbed in with it if you knew what was good for you — everything looked so deliciously relaxed in there — and enjoyed the gentle lateral movement, the off-chop now fatter and slower still, with other guitars that extruded melody from the rhythm in snaky counterpoint to the singing, licking at the vocal parts like a slow summer tide licks at a populous beach. Rocksteady was very much a song-based form, and they were uncomplicated songs at that, and it cemented into place the undecorated Jamaican idea of what makes good singing and the abiding necessity of referring to (but not copying) the new American ‘soul’ style, which still flooded the airwaves from its outposts in Memphis, Houston, Atlanta and New Orleans. Jamaican voices had at last got rid of their English accent.

Reggae, though… How did rocksteady evolve into reggae, a mere two years later? What changed in the music, objectively, allowing The Paragons’ lilting mellifluence to shapeshift into The Upsetters’ hard bite. It was neither a revolutionary cataclysm nor a formal handover; rather, a gradual crossflow from one eminent form to the other. Indeed, it was sometimes difficult to tell what was tough rocksteady and what soft reggae. And when the rocksteady skin finally sloughed itself off after a couple of years, there was an almost identical (but quite different) thing left behind in the sand which required a new name. Yes, it is usually possible to tell rocksteady from reggae, even with the lights on, but that’s not the same thing as being able to articulate what the differences are.

Well, I am here to tell you that the differences between the old form and the new are both real and almost impossible to delineate, certainly given the limitations of my musicological abilities. But let me offer this much at least.

Rocksteady and reggae are very close cousins indeed and the differences between them are far more tonal and temporal than the result of radical changes engineered into the music’s formal structure. Rocksteady belongs vividly to the newly independent country of Jamaica as an expression of its hope in becoming what it wanted to be: it is usually gentle in aspect and sensual in feel. It rocks steadily but very, very surely on the antiphony of the rhythm guitar, now warmed up and slowed right down to simulate perhaps the rocking of a boat on the edge of a current or the languorous shiftings of sun-drenched sex. Its themes are more often than not romantic and its inclination is to loaf in the sun with a rum punch in skimpy but brightly becoming raiment, gently frittering the time, as if it had far too much of the stuff to not waste it deliciously. That is a caricature but not an unfair one, I think. I love rocksteady for all the attributes mentioned and for one thing more: rocksteady insists that all the different elements of its musical structure should pull together to create a tightly unified pocket of rhythm, hemmed close and focussed on repeating that tightened object as a continuum that goes on for ever: ’-cha ’-cha ’ -cha ’-cha… Really good rocksteady records never feel as if they are anything other than a solid singularity — and much of the tension generated by those articulated off-beat chops arises from the feeling that the off-chop is the centre of the music as well as its animating force and its ground.

What can I use as a paradigm? The Paragons, of course, a vocal trio who really were the Paradigmatic Paragons for their bang-diddly demonstration of all the best qualities of rocksteady method in a perfect bundle of sun-soaked joy-in-living. You know “The Tide is High” of course, and I can’t imagine you haven’t heard “On the Beach” too — and you will certainly have smiled and noted its affinity with doowop as a part of its debt to American R&B. ’Nnn-cha ’nnn-cha ’nnn-cha… the groove is irresistible and everyone is leaning into it because it feels so good, chopping on a solidly swinging bass and drum chassis, thunking down on the third beat in the bar because… because that is how it works. And that, in the end, is the reason for its existence. It ties the world into its unitary good offices: we all want to be part of the union. It is always justified, rocksteady, and it always feels right and good.

Reggae wants to do something else. It wants to pull apart, not condense into a solid whole. It has an inbuilt drive, as a necessary element in its sprung nature, to test itself at all times, to ensure that that tensioned spring stays sprung to the finest tolerance … yet never actually released. Reggae could easily fly apart, like a watch-mechanism or a universe, and that is always a risk. But it never happens. It doesn’t happen because the tension it expresses is a perfect description of the Jamaican life — not as it is dreamed but as it really is. Reggae feels less supple than rocksteady, more articulated. More mature. It certainly began at a faster tempo than rocksteady, but reggae has always been somehow less solidly centred, metrically speaking. If you try to count it in fours — which is of course the correct way to go about it— then you find very quickly that it has two tempos going at once and that it is decidedly tricky sorting out which is the principal. The fast four seems often to roll with the guitar, hi-hat and keyboard part while the slow one, its step suggesting a gait that advances at half the speed of the fast one but covering the same distance in time, feels as if it has an affinity with the phrasal trajectory of the bass — the bass which becomes ever more prominent with every passing year into reggae’s superfast evolving future: better instruments and better amplification, recorded better, skanking eights over fours with the big kickdrum thunk coming on the three of the fast four. Reggae is essentially asymmetrical. As every rock drummer has found to his or her dismay, if they try to play reggae symmetrically in the rock idiom, it instantly ceases to feel even remotely like reggae. If the drummer’s any good, the feeling is R&B again — and in Jamaica in the late 1960s, R&B was really a thing of the past, unless you were old folk.

The young Scratch expended the first half of the 1960s working for and then picking fights with his employers, initially the autocratic Clement ‘Sir Coxsone’ Dodd, boss of the estimable but limiting Studio One (Perry was his studio gopher with big ideas of his own, to whom Dodd donated valuable studio recording experience, to Perry’s great benefit); then with one of reggae’s coming men, Joe Gibbs, whose instincts were rather more commercial. Scratch’s first decent-sized island hit, “People Funny Boy” (1968), was an obvious lash-out at some individual who had displeased the now 32-year-old Perry. It is said to have been Joe Gibbs, presumably in part for his use of the condescending phrase that constitutes both hook and title; Dodd meanwhile was the target of “Run For Cover” (1967). These were two of reggae’s opening salvoes: the mellow, agreeable swing of rocksteady is no more to be felt in these skanking blades than Handel is detectable in door chimes.

So here is another vital principle of difference between rocksteady and reggae: the way in which they describe the world — one is a love machine puffing a steam of optimism over a society embracing its new sovereignty; the other might be said to constitute the social-realist’s response to such sentimental hogwash, just as reality bites down hard when it does. Reggae, from its first upbeat, was an adaptable tool for use by the realist and, on occasion, the surrealist. In the face of that show of teeth, rocksteady was gone in an airburst of dust and sunset, while reggae, the impoverished country boy with a mean streak, hitched its trousers, spat on the stones in its pathway and rolled into town looking for trouble.

If you would enjoy the exercise, then you might take the time to examine the hardest edge of the new music as it was embodied by a group of young men you might have heard of, who descended upon Perry in 1970 to record a hefty catalogue of songs which included first or second efforts at what would become international hits over the following decade. The Wailers were involved in the cutting of 110 songs with Lee Perry, many of which are as tuff and sprightly as reggae ever got, some of which are dull and clunky. This was of course before those international hits started to flow in 1973 with further recording at the expense and direction of Chris Blackwell’s Island records, most of which I admire hugely. A handful of the Scratch-produced songs are, however, the best that Bob Marley ever got.

The young Lee Perry, more than any other producer of his generation, looked hard at the structural implications of the sharper, leggier new reggae music, no doubt skanked around a bit to it, sticking his belly out and picking up his feet like a duck, and found in the inner works of the form a geometry that was alive with possibility, especially if you treated the whole apparatus as a living thing. An organism.

I THINK THIS is the key to the Shakespearean genius of Scratch: the understanding that music can only be good and true when it aspires to the condition of something that lives, at least in some of its parts. There is seldom dead space in a Scratch recording, although there is no obvious shortage of empty space or repetition or the ferocious stripping out of wood, dead or otherwise. There is also the curiously organic effects produced through the limitations imposed by the four-track TEAC tape-recorder used at the Black Ark — a typical simplifying decision made by the producer-engineer at just that point in history when the 16-track studio array was coming on line everywhere it seemed but in Washington Gardens.

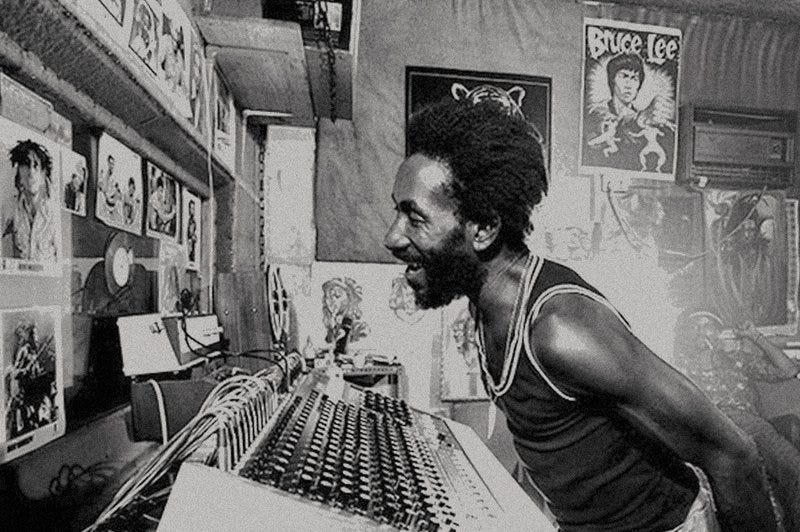

The four-track had innate virtues, though, other than its cheapness and robustness. In the hands of The Upsetter it became a tool for the growth and nurture of a kind of musical flora that expanded and deepened into a sonic jungle of squelchy, mouldering organic textures, life squeezed into them through the rather odd old-fashioned recording practice of ‘bouncing down’. As I understand it, bouncing down essentially entailed new layers of music being loaded on to tracks that were already bearing the burden of prior bounces. This engendered a degree of opacity unwelcome to many in an age of prestige ‘hi-fidelity’ and growing interest in audio for its own sake. The 16-track recording system had been developed to render four- and eight-track obsolete by allowing space for a significantly increased volume of instrumentation and voices, which not only enhanced separation but also offered more scope in the way of overdubbing and, at a later stage, final mixdown. Listen to any of the great latterday creations of the Ark for examples of this ‘organic’ integration — try the mesmerising rotary formations lending an element of alien chunk to Junior Delgado’s brilliant, but otherwise Spartan, “Sons of Slaves” (1977, the long version) or simply turn to the extraordinary Upsetters album, Super Ape — and you will hear thick mulches of unspecified instrumentation where, because of the bounce-down, you’d be pushed to name one of the instruments in the quagmire, let alone all of them. There is something profoundly organic about the sound that emerges to attach itself to the hard wood-popping of the drums (as if it were some kind of fungus or mistletoe affixing itself to the branches of a tree), and it strikes me that there is something of the greenhouse and the potting shed in Scratch’s method. You might say that his interest above all lies in how music grows, in all its muck and fertility, and how it mutates or bears fruit. He said it himself, plain as plain, that strange afternoon when I interviewed him in the presence of his Swiss wife and a large number of Christmas decorations: “Mess is energy. That's the life source of the energy of the earth. The mess. You come first with piss and shit … as a baby.”

What follows is an edited extract from that interview I sort of conducted with Scratch in 1997 for the Independent, when I was thirty-seven years old and greedy for Perry’s music. This was also the year of the birth of my first child and I suspect that somehow, at some unconscious level, I wanted Scratch to be someone he evidently was not, nor felt obliged to be. Quite rightly. And indeed he did not behave like the kindly wizard-grandad of my fond hope. In fact, at no stage of the discussion did I feel that he perceived the goblin-eared man sitting opposite him as anything other than an ‘object’, in the psychoanalytic sense of the word: either I was going to meet his needs or I was not, in which case who knows what might happen?

I tried very hard to meet his needs.

LEE PERRY IS an inscrutable little man. He is in his early sixties and seems entirely spry. He favours clothes and hats adorned with CDs, icons and bits of electronic hardware. On the day we meet in the basement of a record company outpost in Notting Hill, he has on a pair of trainers and crimson athletic tights. He sits up straight on his chair like a well-behaved child and fiddles occasionally with a video camcorder he has set running at his feet, focussed on the contents of a suitcase from which spills a tangle of wires, papers, fairy lights and Christmas decorations.

I ask him how he finds England these days, given that he's lived in Switzerland for years. He turns a pair of tilted, almost whiteless eyes to mine and declares, "England is my country. Is no longer ruled by the Queen but is ruled by my music and my theocratic government — and ganja Rastafari." He then gabbles through a litany of conquests and correspondences between parts of the body and elements of the rhythm section, routines I’ve heard many times before; he talks about the importance of children, computers, and the evil power of boredom. He explains how his music comes from outer space, and that he, Captain Lee "Scratch’ Perry is "the master of the pounds, shillings and pence, taking over from the US currency department.''

I ask him what he recalls about his relationships with the principal figures he recorded at the Ark: Max Romeo, Junior Murvin, the Heptones, Junior Byles, the Wailers?

"Well," he continues, "we were creating a spiritual army to take over from the heads of government, and take over all the money. We needed young boys who want to fight spiritual warfare in the battle of the Armagideon war. They were learning from my music, the Ark of the Covenant, the Sunship of Fire."

Nowadays Scratch is of the Christian faith, following his rejection of Rastafarianism around the time of his trouble at the Ark.

"Fully," he confirms. "Here's my teacher." He fishes a dog-eared image of a white-skinned Jesus from the suitcase. "He is my angel."

I read somewhere that you have mosquito angels...

"Yes," he says and laughs. His Swiss wife, Mireille, joins in the laughter from her sofa. Perry then expounds on the rottenness of much of the world and how he and his space army are going to rescue it from corruption. He is looking for more volunteers. "We can help you humans to make it right on this planet." He points at my somewhat elephantine ears. "And you must understand this or you would not have those."

I ask him if he likes living in Switzerland.

"I would be very old and ugly if I didn't live in Switzerland," he says. "I like it because of the mountains, the stones, the visions. Not much pollutions. In England I feel the poisons."

Is poison the reason you destroyed the Ark?

He pauses to think for the first time since we started talking. "I was given the part of Noah to build the ark. So I was calling the animals and some of the animals hear me. But on the ark, some of the animals turn out to be cannibal and eat the other animals. And Noah said, `What the hell am I doing here?' So I burn down the ark, because I cannot support cannibal. It's too dread," he says simply and looks at his suitcase.

I ask him why he carries around a suitcase full of Christmas tree lights. "That's my eye," he says. You take it wherever you go? "Of course. I do not want to walk around in darkness."

Perry has said before that he likes records because they are made of black vinyl, which is the colour of shadows. How does he feel about compact disc?

"CD explain who I am," he says, holding his hat up to the light so that the CDs on it glint. "When you look in CD, you see I. I am CD. And I would rather be CD. Or DD — doo-doo…" He giggles, as do Mireille and I.

We turn to his relationship with Mireille, who, she says, rescued him from his increasingly perilous day-to-day life in Kingston after his breakdown.

"She is my wife and my knife," says Scratch. "And also my cloak and my dagger. We met in Jetstar." Jetstar is a distributor of reggae records in Harlesden.

"I took him from a place where he was not supposed to be," says Mireille, referring to her subsequent rescue flight to Jamaica. "He was calling for help and I had to go — take him from hell to a place where he can be safe: eat properly, put life in order, look after body."

"She is a great torturer," interjects Scratch. "She want to execute anything of dust. She is the enemy of dust and ashes. But then she has to take my mess."

"He tortures me with mess," says Mireille. "I am clean and tidy and he's messy. So he has to learn to be clean, and clean the toilet every time. And to find salvation, we have to move to a house where he can have his own area, where I don't have to put up with mess."

"If I don't make mess, it not lovely. If you don't let me make mess, you in terrible trouble," says Perry. "Without mess I cannot work. You know why? Mess is energy. That's the life source of the energy of the earth. The mess. You come first with piss and shit, as a baby."

He then moves on. He reaches into his suitcase and comes up with a picture of Charlie Chaplin, which he shows me.

"Bring back Bruce Lee," he says.

Is that Bruce Lee? I say, rather dully, I realise like a weary parent humouring his recalcitrant infant.

"In his other form," says Scratch.

In his Charlie Chaplin form?

"Bruce Lee," says Scratch, as if to an idiot, "is coming back as Charlie Chaplin."

We all laugh and decide it's the end of the interview. He presents me with a farewell gift, a chocolate Christmas tree bauble wrapped in blue shiny paper. "It's a chocolate from Mars," he says. I thank him and ask if it's OK to keep it for later. He doesn't seem to mind.

THE GALACTIC IRONY is that many of Perry’s mightiest works have a Martian quality to them, as a modern poet would understand the term. For the ‘Martian’ poet, everything material is experienced as if it had never been encountered before. Ordinary things, to Martian poets, are not necessarily weird, but they do have something about them that causes the poet to see them as he would were he a little green man. And Martian though he may have seemed to some observers, Perry himself always insisted that he was native to the planet Saturn. This has seemed perfectly fair enough to me, given his natural affinities. Saturn is as good a planet as any gas giant on which to imagine yourself dribbling, having your nappy changed, enjoying the mysteries of potty-training. Rather Saturn than Mercury or Pluto for that profound ritual. And certainly, no other planet can reasonably claim to match Saturn’s powerful charisma, most obviously manifest in its famous rings, which are largely composed of ice particles (wouldn’t you just know it) and has no less than 274 moons. Plus, as a young adult, Perry may well have enjoyed the opportunity to explore the foundational Afrofuturism of the greatest Saturnian ever to materialise on our blue dot, the big-band leader Herman Blount, who is best known by his true name, as we all should be: Sun Ra. He of the eternal Arkestra.

Scratch was incapable of letting things be as they ‘should’ though. Reggae is by no means as formally flexible as modern jazz, certainly not as it was practiced by Ra; neither does it lend itself felicitously to the kind of musicianly improvisation that so distinguished the Arkestra at every stage of its life on earth. Reggae has always to observe the rigid imperatives of its form; it has to do that, otherwise it ceases to be reggae, with its abiding concern for danceable rhythm. Tonality is important, but the geometry of time and space is its primary directive, and while accomplished soloing players can certainly set out for the farther reaches of what in the 1960s was becoming an increasingly busy old galaxy (you couldn’t move sometimes for tough hombres making saxophones squeal), the rhythm remains itself implacably, or its ghost does. In Roots as in Dancehall reggae, the rhythm is how a track is identified. It is what a track is. In reggae, by and large (and regardless of what Sly and Robbie might have to say about it), musicians are not the principal innovators; the studio engineer-producers are.

Perry’s first serious experiments with what would become universally known as ‘dub’ took place in 1973, building on the established practice of putting instrumental ‘versions’ on the B-sides of singles. Rhythm Shower was an album almost entirely composed of instrumental ‘versions’ which had been in many instances subject to the producer’s mixing-desk tweakings. Not quite dub as we know it but an anticipation of it. Blackboard Jungle in Dub was the first use of manipulated deep reverb that I know of. Here were clear indications that Scratch was a creative formalist — an intuitive studio improviser whose reflex it was to see a conventional boundary and treat it as an opportunity for playful transgression with the knobs and faders on the mixing desk plus other kit— while also remaining absolutely observant of the primacy of the bass and the drum. The music, or parts of it, in Perry’s conception of dub often appear either to be upside down or the wrong way round or made of stuff you can’t quite name or define. Or something’s gone missing, or there’s too much of it. Or, through an incomprehensible sleight of hand and ear, the music has been turned inside out somehow and exposed to rays other than those emitted by our own sun.

Furthermore, with Scratch, one tends to be visited by the feeling that you’ve ‘never heard anything quite like that before’ — it is rare, for instance to find a Scratch dub completely swimming in lazily applied repeat-echo. This was the case really until the latter days of the Ark, say 1976-78, when it was plain that major labels and their artists began to ask for Scratch readymades, such as the ‘trademark’ rotary churn he introduced to the rhythm exemplified by the work done for Gregory Isaacs’ “Mr Cop” (if only Scratch had been involved with Gregory on more than that one solitary occasion…) and the Jolly Brothers’ lush “Conscious Man”, which came close to being an international hit: pop-reggae with a real soulful tug in its galoshes. At an informed guess, this extraordinary in-and-out tidal-sloshing effect is a composite sound contrived by lining up a Chorus pedal at source (on a guitar, one assumes) further adulterated by a basic, possibly Scratch-built phaser and then aired through a rotating Leslie cabinet. Reader, you will hear a reggae studio band (at least the harmonisable parts of it) turn to churning flux before your very ears — and for a while there was too much of it about, because it appeared that everyone wanted their rhythms doused.

THERE IS A multitude of reasons why it is unlikely that this strange, elusive and oddly unremitting persona could have been a product of, say, the suburbs of Guildford in the 1930s. But the most compelling reason of them all is that he simply could not have been given life anywhere else on our planet but a small rural parish on the large Caribbean island of Jamaica. It is the most important thing about him as well as the most obvious thing: he was a Man of Jamaica, a creature of that remarkable island’s history, its contradictions, its faiths, its fears, its collisions of culture: obeah (a tradition of healing magic originating in West Africa), scripture-based Old Testament Christianity, folk myth, rhythm, rum, weed, fish, cornbread, duppies (ghosts), post-colonial politics and Rasta. Perry’s perceptions were forged in an environment that fostered belief and superstition as well as ritual, which is to say that every object encountered in the world is met as if it were endowed with mystery — everything and anything can express the sound-poet’s mind in the moment of capture by language. Things are seldom precisely as they seem. The world Perry really did inhabit was so charged with the electricity of his curiosity, and consequently modified to accord with the needs of his imagination, that it is almost as if the world and its objects are made anew every time he re-enters it from whichever dimension he abides in when not actually visible to the naked eye (take his wife’s kitchen in Switzerland, for instance). It is said that he died in 2021 and good manners dictate that we must take it to be true. He was 85.

But it would be wrong to suggest that Lee Perry’s music is completely unique in every aspect and dimension. Nothing can be that, not if played on conventionally tuned Western instruments. Indeed, the only enjoyment I ever got from music that I could honestly say was unique in my experience was a concert of Japanese music I attended hundreds of years ago in a place I cannot now call to mind. I had never heard music that was tuned that way, that appeared to be regulated in time so differently and seemed, naturally enough, to be shaped by a completely alien syntax. On reflection it is clear to me in feeling at least that Scratch would certainly have dug it.

But there are individual sounds and combinations of sounds, when encountered within the province of the right kind of musical environment, that do really amount to an experience for which the word unique is perhaps not inappropriate. I don’t mean the signature sounds and playing styles that indicate the presence and creative intentionality of distinguished players — Coltrane’s ferrous tenor sax, Keith Richards’ early 1970s Telecaster set-up, Björk’s voice etc — but sounds that are so particular in their function in the music that they might be said to be unique to that musician’s vocabulary.

I am thinking now of Scratch’s kick or bass drum sound, which he used pretty much continuously in the five years or so that he was captain of the Ark. That drum sound has no parallel in music as an anchor-point for floating cloudbanks or running water or the ships that sail in either or both (or the sailors who are sailing in the ships). Scratch’s kickdrum is, I think, inimitable. It is damped to the very brink of sogginess and the drum is always mixed high and dynamically close (with plenty of ‘air’ around it) to its chief associate, the bass guitar, which needs the kickdrum as it were a parent. And it almost invariably functions psychologically for the listener as an anchorpoint for his or her experience of the music as an event mobile in time. The kickdrum thudding dully but reassuringly on the three is the feet the music walks on and the safeguard the listener lives by, moment by moment. That magnificent edgeless thud is all the confidence you need to know that the great ship of life is moving forward with grace and eloquence into the future. Its future and yours.

THE FOLLOWING IS true in every detail.

I have been unable to hear music of any kind since the onset of Sudden Neurosensory Hearing Loss nearly three years ago, for the third and I would think last time. I am severely/profoundly deaf. Such is the peculiarity of the damage done to my vestibular system that music can be ‘heard’ but not enjoyed at any level whatsoever. Music sounds appalling. It is without tonality, reliable rhythm, stable timbre and all of it is insulted by the surface distortions we associate with aggressive tinnitus, vestibular migraine and a damaged stylus on the turntable. You could play me a long list of songs I love and I would not be able to identify any of them, except by guessing.

Nevertheless, over the past few months there has been something of an improvement across the upper band of the low frequencies in my residual hearing. I discovered this in the funky greengrocer at the end of my road, where they have a bit of a taste for hip-hop, jungle and other varieties of the many rhythm-based musics which dominate our real-world musical agenda so thoroughly and satisfactorily (even though I can’t keep up with developments, for obvious reasons).

I was standing in the queue with my wife waiting to pay for the customary legumes when I suddenly became aware that I was listening to the bassline and beats of whatever otherwise-unrecognisable piece it was. And they made sense as music. The bass was roughly, sufficiently tuned, if a little approximate and wobbly; but the kickdrum beat, which didn’t need to express pitch in the same way, was smack on the money. It sounded like a kickdrum and I knew it to be one too.

“Fuck me, Jane,” I said. “That drum … it sounds like … like a drum!”

And since that afternoon I have been listening systematically to every Lee Perry record I have accumulated over fifty years. Listening to the kickdrum and the bass and trying to exclude or ignore wherever distorting fog or mulch or hell or highwater impinges on it as texture to the rhythm — and you must believe me when I say that Scratch’s kickdrum is the most beautiful sound I have ever heard. It is. It’ll keep me going for quite some time, I think.

Thud.

Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry for beginners: a small accumulation of thuds

Junior Murvin: ‘Police and Thieves’

Could there ever be such a thing as a Daddy Scratch Rhythm? If it were possible, it might well be this one, by popular acclaim and even perhaps following deep analysis by reggae boffins. This is the Scratch sound as it was in 1976 — one of his great years — lithe, propulsive and dread as a simple three-chord structure could ever be. Its locomotion is like unto a train passing through the darkness of a Jamaican night and its tiny repeat-echoed hiccup is a classic touch of Scratch genius. No one has ever claimed Junior Murvin’s falsetto as a top voice and it is an interesting Scratch peculiarity that he worked so often with voices that were characterful rather than great. I suspect he was really only interested in voices that folded into his mess agreeably. Look out for dub versions of “Police and Thieves”, the primum mobile being “Grumblin’ Dub”.

Junior Byles: “The Long Way”

If Scratch did have a favourite voice then it might well have been Byles’, whose extraordinary pipes cleaved to Perry rhythm like a vine to a crumbling wall. This is fabulous. There are several versions (as well as ‘versions’) but my preference is for the one to be found on Trojan’s 2CD collection of Scratch’s ’70s 7in singles, Sipple Out Deh: The Black Ark Years. It’s a brilliant survey of the basic currency of reggae comms: the 45rpm 7inch single

Lee Perry The Upsetter: “Big Neck Police”

Scratch was an actorly singer — and if you can cope with his singing then his very fine Roast Fish Collie Weed & Corn Bread album is a place to hang out, because it includes loads of gorgeous kickdrum action with lots of air round it. This is an umpteenth rendering of “Police and Thieves”’ nearest rival for Daddy Scratch Rhythm, the heroic “Dreadlocks in Moonlight” / “Green Bay Incident” spook-out. See also the wispy beauty of the relatively recent but already hard-to-find Pressure Sounds dubplate compilation, Sound System Scratch, where it goes by the subtle identity of “Big Neck Cut”.

Finally, if you are an album person and you want a touch of longform Scratch then there are two places to start, again from the vintage year, 1976: The Upsetters’ marvellous vegetative Super Ape and Max Romeo’s War Inna Babylon.